.

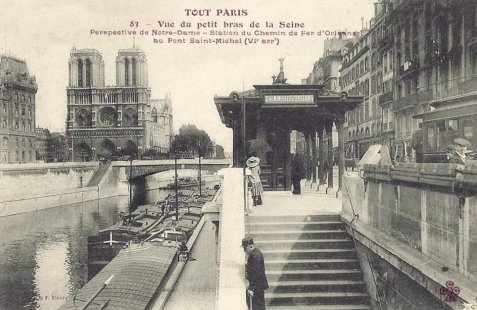

In the heart of Paris lies a tale as complex as the city itself: the story of Paris Sûreté and its legendary founder, Eugène-François Vidocq, the criminal who became the first modern criminologist.

An investigation bureau composed of undercover officers was established in 1812 under the name Brigade de Sûreté ((French for “safety” or “security”). Its head, Vidocq, spent the first fifteen years of his adult life either in prison or on the run. He was a poacher turned gamekeeper, a genius innovator—and later a best-selling author—whose adventures captured the imagination of his contemporaries, and inspired many renowned writers of his time.

Vidocq was born in 1775, a baker’s son. His was a perfectly ordinary and relatively well-to-do family in Arras, northern France. However, ordinary life was not good enough for Eugène-François. By fourteen, he had sold off the family’s finest china to finance his quest for adventure. He ran away, heading for America. Unable to afford the voyage, he joined a travelling circus as a human cannibal. This unusual career ended when he refused to eat a live chicken and got a beating.

The boy ran away again. He joined an itinerant puppet show, but was caught in bed with the puppet master’s wife. After taking a few more unexpected detours, he returned home a repentant yet unchanged prodigal son: a womanizer and fan of drink and brawls. Father Vidocq, disappointed with the young man’s behavior, was glad when his troublesome offspring joined the army.

Like his previous employment, Vidocq’s military career was short-lived. Flighting and hopping from regiment to regiment, once deserting to fight on the enemy’s side, he ended up in a roving militia composed mostly of petty criminals and deserters. Until the age of thirty-four, Vidocq spent most of his time in and out of prison. He escaped from all France’s galleys and more than twenty prisons under different disguises, including that of a nun.

.

Galleys were ships recycled as prisons. Cramped conditions, appalling lack of hygiene, and forced labor awaited the inmates.

.

In 1809, residing on a galley once more, and realizing his life was a vicious circle, Vidocq decided to reform. In exchange for his liberty, he offered to act as an informant. He was sent to a regular prison, where he gathered information from his fellow inmates. Happy with his work, the authorities promoted him to head of a newly formed unit, the Brigade de Sûreté. Its agents were responsible for apprehending murderers, forgers, and thieves, securing stolen goods, and arresting escaped convicts.

.

‘

The institutionalized police force was still in its infancy, and the resourceful Vidocq became an innovative criminalist. He developed policing methods still widely used today, including crime scene security, detailed written records, indelible ink and unalterable bond paper (he held patents on both), ballistics (the flight characteristics of bullets), sending undercover agents to prisons to familiarize themselves with convicts susceptible to re-offend, or preserving footprints with plaster of Paris. Vidocq’s Sûreté laid the foundation for Scotland Yard, established in 1829, and also served as a blueprint for the FBI a century later.

,

The first agents, men and women, were questionable characters. The “Vidocq’s gang”, was a common nickname for the Brigade de Sûreté at the time

.

The very successful Vidocq’s team grew from four to twenty-eight agents. Most of them were ex-convicts. He did not hesitate to recruit women: a step Scotland Yard took a whole century to adopt. The Sûreté faced ongoing scrutiny due to its agents’ questionable backgrounds. Complaints were brought to the attention of Vidocq’s superiors that he and his team were taking bribes, engineering crimes, and profiting from them. As a fact, when Vidocq left–before being forced to leave–in 1827, he had half a million francs to his name. How he amassed such a fortune on his police officer’s salary is everyone’s guess.

.

.

With time on his hands, Vidocq set to work on his memoirs. They were an instant hit and attracted new friends. Dumas the Elder, Hugo, Balzac, and other literary giants dined and wined Vidocq to hear more of his exciting and inspiring tales. The memoirs, translated into English within a year, eventually gave birth to the detective novel and the true crime genre on both sides of the Channel.

.

.

Although Vidocq’s memoirs are embellished for dramatic effect, and not entirely reliable, they remain valuable historical documents. One of the most fascinating aspects of the memoirs is the insight into the criminal underworld of early 19th-century France. Vidocq provides detailed descriptions of the various criminal gangs and their methods, offering a view of the social and economic conditions of the time.

Vidocq’s own experiences as a criminal led him to advocate for rehabilitation over punishment. He understood that social and economic circumstances pushed many individuals towards crime. This perspective influenced his efforts to recruit former criminals as informants and undercover agents, giving them a chance to reform. He called for improvements to prison conditions, including better sanitation, education access, and vocational training. His ideas and actions laid the groundwork for modern approaches to law enforcement and criminal justice.

Vidocq put his theory into practice after leaving the Sûreté by founding a paper factory with a workforce composed exclusively of former convicts. The experiment was unsuccessful, and Vidocq became bankrupt. He returned to the Sûreté where his absence had been noticed as crime rates shot up after his departure. From a mere agent, he was soon reinstated as chief. His second tenure was of short duration – a mere six months – before he was forced to resign again.

,

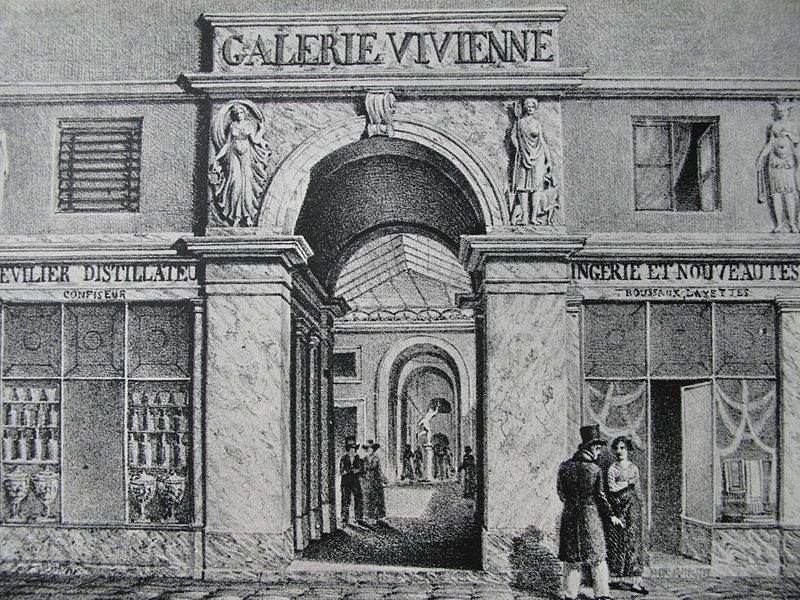

The Gallerie Vivienne, a prestigious address on the Right Bank, was chosen as the seat of Vidocq’s detective agency, the first of its kind

.

Soon after his demission, Vidocq founded the Bureau des Renseignements, opening another new chapter in crime history by introducing the concept of hired investigators. This gave birth to the private detective job. Vidocq’s detective agency offered a wide range of services from surveillance, background checks, undercover operations, and forensic analysis to delicate bedroom secrets.

Just as he did with the Sûreté, Vidocq introduced several innovations. He continued to refine his use of disguises and undercover work, employing these tactics to gather information and solve cases discreetly. He continued to emphasize the importance of meticulous record-keeping and documentation.

The Bureau des Renseignements benefited from its founder’s fame. It employed forty agents and saw many clients a day. Alas, Vidocq’s unconventional methods and controversial past did not please the powerful, and police repeatedly attempted to destroy his business. Fraud was mentioned, along with corruption of civil servants, defamation, usury, selling honours, stealing letters, providing substitutes for conscripts hoping to avoid military service, and many other offences. While Vidocq was ultimately acquitted by a public jury, two lengthy and costly trials and the confiscation of his precious files forced him to close.

In 1845, aged 70, and with his fortune lost, Vidocq travelled to London, in the hope of opening up a private detective agency. That project did not materialize due to funds shortage. In reduced circumstances, he wrote letters to the new Sûreté head appealing for a government pension.

When Vidocq died, aged 82, his assets amounted to less than three thousand francs. Even after his death, he managed to create trouble when eleven women claimed to be his sole beneficiaries.

Vidocq continues to live in many reincarnations, both in literature and in movies.

.

Related posts:

The Policeman’s Work Is Never Done

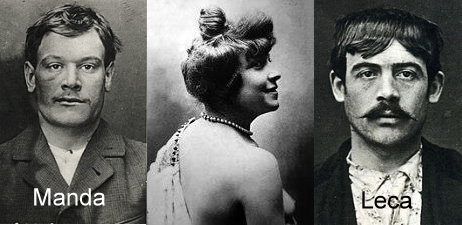

Casque d’Or: The Low-Life Femme Fatale

,

READ MORE BY THIS AUTHOR: