Readers who remember the O.J. Simpson’s trial fever will have a small idea of the immense frenzy that surrounded the Bloody Trunk Affair in 1890. Never was there a murder case where a suspect in custody was cheered by the crowd, thrown flowers, blown kisses, exchanged hand-shakes with officials and reporters, travelled first-class, displayed elegant gowns, and enjoyed gourmet food. The four-foot eight waif Gabrielle Bompard (21) did all that after having admitted that she was, indeed, somewhat guilty of murder.

Gabrielle grew up in Northern France, the daughter of a widowed metal dealer. A burden to her father’s live-in mistress, the young girl was dumped into boarding schools and convents where she repeatedly misbehaved until she was sent packing. Finally, at her father’s request, she was locked up in a corrective institute where she remained until the age of twenty.

Once released, she decided to seek fortune in Paris. The little money she had brought with her soon ran out and it was then that her path crossed with that of Michel Eyraud’s. She became his mistress. In his fifties and no longer handsome, Eyraud proudly displayed his youthful paramour in the boulevard cafés. Once an army deserter, he had spent many years in the Americas until an amnesty allowed him to return to France. He spoke several languages and was an accomplished crook. At the time he met Gabrielle, his bumpy business career was nearing its end and he would soon be accused of fraud unless he found enough money to plug up the hole. He turned to Gabrielle for help.

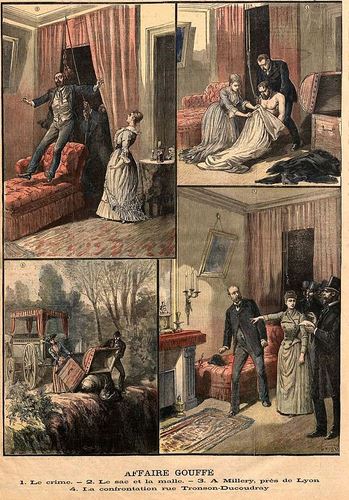

The plan was simple: Gabrielle was to lure a rich man to an apartment where they would rob and kill him. As modest as the plan was, its execution was anything but. First, the would-be murderers travelled to London, where they purchased a trunk large enough to accommodate a human body. Next on the shopping list was fabric to sew into a body bag, followed by a rope, a pulley, and a silk cord to use as a noose. Back in Paris, Eyraud hammered the pulley into a crossbeam and installed a curtain across an alcove to hide a chair and the hanging rope. Here he would wait for the victim. Now the couple only needed to snare a man known for carrying large sums of money and susceptible to the lure of the fair sex. Among their boulevard acquaintances, they chose Toussaint-Augustin Gouffé, who was manifestly interested in Gabrielle’s charms. Gouffé was a skirt-chaser extraordinaire (investigation revealed that during the month before his death he slept with twenty women) and he readily accepted Gabrielle’s invitation to a romantic candle-lit evening.

At first, everything went according to the plan: Gabrielle, clad in a dressing gown tied with the cord, skillfully maneuvered Gouffé onto a chaise longue next to the curtain. Her role was to playfully tie the silk cord into a noose and slip it over the victim’s head. Something went wrong at that moment. Gabrielle froze, as she later claimed, and Eyraud brutally took over. In the subsequent struggle, the pulley gave under the weight of Gouffé, who crashed to the floor and had to be strangled by hand.

At first, everything went according to the plan: Gabrielle, clad in a dressing gown tied with the cord, skillfully maneuvered Gouffé onto a chaise longue next to the curtain. Her role was to playfully tie the silk cord into a noose and slip it over the victim’s head. Something went wrong at that moment. Gabrielle froze, as she later claimed, and Eyraud brutally took over. In the subsequent struggle, the pulley gave under the weight of Gouffé, who crashed to the floor and had to be strangled by hand.

Gabrielle spent a sleepless night alone with the trunk containing Gouffé’s body, while Eyraud rejoined his marital bed. His unsuspecting wife later reported that he snored loudly that night. In the morning, the couple hired a cab and had the trunk transported onto a train to Lyons. Once there, they rented another vehicle and drove to a remote place above a river. They dumped the body down the steep embankment, after which Eyraud destroyed the trunk and disposed of the debris further down the road. Now was the time to start anew in another country.

The couple landed in Dover as Monsieur Labordère and his teenage son. The petite Gabrielle, her long hair chopped off, made a convincing boy. Several days later they boarded a transatlantic steamer heading for Canada. They were now known as E.B. Vanaerd, a wealthy businessman, and his daughter Berthe. They travelled from Québec to Montréal, and on to Vancouver, to end up in San Francisco. Along the way they met Georges Garanger, a wealthy Frenchman. Garanger immediately fell under Gabrielle’s spell, which was most convenient as Eyraud needed another victim to fleece and kill. Completely confident in Gabrielle’s obedience, he allowed the pair to travel East, presumably to meet Gabrielle’s aunt and settle an inheritance. He planned to wait for them in New York and to kill Garanger there. It was a fatal error. Gabrielle, tired of Eyraud’s frequent brutality and in love with the handsome Garanger, warned her new lover as soon as they were out of Eyraud’s reach. Instead of going to New York, the two diverted to Canada and from there to Europe. During the voyage, Gabrielle slowly unburdened herself, but Garanger did not fully grasp the reality until they reached Paris.

Meanwhile in France, the investigation of Gouffé’s disappearance started without a clue. Weeks later, a decomposed body found near Lyons

was connected to the missing man thanks to the intuition of François-Marie Goron, the brilliant head of the Paris Sûreté. Goron did not hesitate using the press to gather information from any member of the public willing to co-operate. The intrigued public was more than willing. When the reconstructed bloody trunk was exposed in the Paris morgue for a week’s duration, thousands of people—Frenchmen as well as foreign visitors—patiently waited for hours to catch the sight. Two names were linked with the missing Gouffé: Michel Eyraud and Gabrielle Bompard, both notable by their absence since the victim’s disappearance in July. The big hunt began, first in France, then in England, and on to America. From each destination, the detectives returned with a wealth of information. There was no doubt whatsoever about the couple’s involvement with the Gouffé murder. Long before Gabrielle’s return to France, both she and Eyraud became the world’s most wanted criminals.

Gabrielle, playing Eyraud’s victim, surrendered herself to the police, the faithful lover Garanger at her side. The press and the public went wild. Perhaps unconscious of the severe charges held against her, she thrived on her fame, or rather infamy. Her every appearance, whether it was a transfer from prison to the Palace of Justice for interrogation, or a trip to the crime sites, drew huge attendance. Her portraits appeared in print, and the most trivial details, from her fashionable attire to the food she ordered, were deemed worthy of public interest. Pleased with so much attention, Gabrielle did her best to charm the crowd.

Waiting in vain in New York, the betrayed Eyraud was alerted by the American newspapers that a French investigative team was on his heels. He quickly fled to Cuba, but his luck ran out. Apprehended in Havana and transported in a cage to France, he knew he was finished. Now that the two criminals were safely locked up, the stage was set for an action-packed trial. Gabrielle pleaded extenuating circumstances. She acted under the influence of hypnosis, she claimed. Eyraud would have none of it. Seething with hatred for her betrayal, he wanted her to share his all-too-certain death sentence. According to him, he never hypnotized Gabrielle; he was actually a lap dog carrying out her orders. However, Gabrielle had an extensive background in hypnotism and many witnesses reported her ability to fall into a deep sleep during hypnotic séances dating as far back as her childhood.

Today, we cannot fully understand the status of hypnosis in the 19th century. Not only was it the playground of the idle classes, but it was seriously considered by respected scientists. At the time of the trial, hypnosis was the battleground of two schools, one led by the neurologist Charcot and his team in Paris, and the opposing School of Nancy headed by Professor Liègeois. “Is it possible that the accused killed under the influence of hypnosis and therefore is not responsible for her action?” was the burning question of the trial. “Absolutely not,” thundered the Paris team. “Absolutely yes,” countered the opponents. In the end it fell to the jury to decide the outcome. The jury knew that by acquitting Gabrielle, they would create a dangerous precedent. However, the accused was young and personable. Some extenuating circumstances could be admitted, couldn’t they? Gabrielle Bompard was sentenced to twenty years of which she served twelve. Michel Eyraud was publicly guillotined soon after the trial. Thus ended the cause celèbre of the Bloody Trunk.

Related post:

[…] Originally posted on Victorian Paris. […]

LikeLike

One of many murder mysteries where the body is stuffed into a trunk.

LikeLike