.

/

Paris, with its grand boulevards, iconic landmarks, and rich cultural heritage, captures visitors and residents alike. Yet, beneath its glamorous façade lies a lesser-known aspect of its history—the Zone. The wide boulevards that run in circles were once moats and defensive ditches surrounding the walls. Names such as Porte de Clichy or Porte Saint-Denis, now mere metro stations, recall the former gates to the French capital.

Permanent construction was prohibited within 250 metres (55 yards) of the fortifications. Outside the protective walls, a no-man’s-land emerged, inhabited by those on the fringes of society. Over time, this area became known as the Zone. This was a place where the destitute and outcasts found shelter amidst poverty and squalor. Rag pickers, beggars, and other marginalized groups eked out a living in makeshift dwellings constructed from scavenged materials. These offered little protection from the elements. Urban amenities such as street lighting or running water were missing.

ies such as street lighting or running water were missing

.

The Zone was a fertile ground for crime and violence, as gangs and thugs roamed the streets with impunity. It was a lawless wasteland, with little hope for a brighter future. The city’s efforts to maintain order and protect its citizens were constantly challenged by the criminal activities originating from the Zone, making it a significant concern for the overall well-being of Paris. The Zone housed the cheapest eating places, the roughest bars, and was the working domain of prostitution dregs. (See the post The Fortification Whore below.)

.

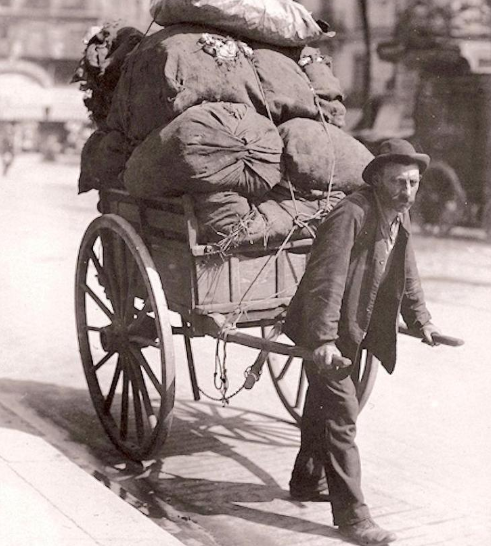

A rag picker

.

Crime was not the only danger emerging from the Zone. The activity of rag pickers worried the authorities as they carried and spread various diseases. Rag pickers relied on scavenging for their livelihood, combing through the streets, alleys, and garbage dumps of Paris. They searched for discarded items that could be salvaged, repaired, or sold. They collected everything from rags and bones to metal scraps and discarded furniture, transforming what others saw as waste into commodities. Long hours spent scavenging through garbage heaps, exposure to unsanitary conditions, and the constant threat of illness were part and parcel of their existence. The child mortality rate in these parts was four times that of the healthier parts of the city.

.

Sorting the scavenged material

.

The Commission for Unsanitary Housing of the Department of the Seine produced a report for 1851 that uses the terms of a report from 1832. The situation does not seem to have changed in twenty years:

Most are busy sorting, during the day, the product of their nocturnal rounds, squatting around this dirty loot. They pile up in every corner, and even under their bunks, bones, old linens soiled with mire, whose fetid miasmas spread in the middle of these hideous garrets, where often a space of less than two square meters serves as shelter to a whole family.

Rag pickers had to be adept at finding solutions to challenges, whether it was repairing broken items, repurposing materials, or devising innovative ways to make ends meet. For instance, they kept records of weddings and other celebrations. After such gatherings, the ground was a source of cigarette butts and cigar stumps. The remaining tobacco was meticulously extracted and recycled. Discarded food, too, could be a source of income. The post Poor and Hungry in Paris: Gambling Eateries and Harlequin Luxury Food describes this industry.

Despite their vital role in recycling and waste management, rag pickers were viewed as social outcasts, relegated to the fringes of society. Their bags could contain stolen items, and they sometimes did. This social stigma only served to further isolate and marginalize them, making it even more challenging to escape the cycle of poverty and deprivation.

.

The recycled goods on sale

.

The history of the Zone offers a sobering glimpse into the darker corners of Parisian society, where poverty and exclusion were stark realities for many.

–

Related posts:

,

READ MORE BY THIS AUTHOR