Health care counts as one of the main reasons why you would not want to live in the 19th century. It is easy to be seduced by paintings and movies. From our point of view of ragged jeans, tattoos, and messy hair, the elegance of tall hats, snow-white shirts, and gloves for the gentlemen, or the lace, silk, and sculpted hairdos for the ladies, paint a picture of the lost perfect word. Ah, if only…

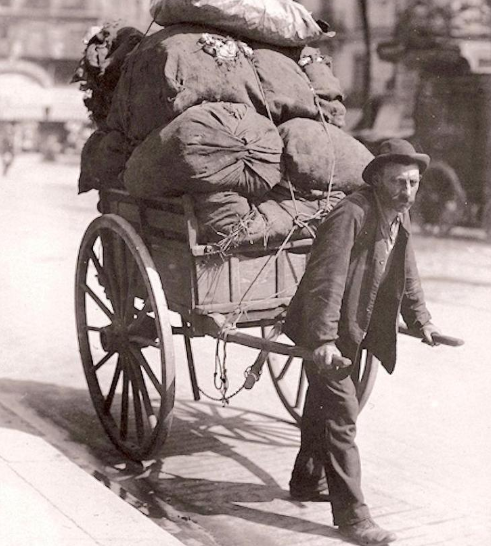

Wake up to the reality of our ancestors’ lives. The snow-white shirts and the lace got rapidly dirty in the polluted air. Heating was provided by wood and coal, both producing ashes. In addition to sooth covering every urban surface, the streets reeked of urine and other byproducts of horse transport. Read Life in the Age of Decay. (All links below)

The beautiful, elaborate gowns were unwashable because they were composites of too many materials, each needing special care. They were maintained by brushing and spot-cleaning; they never saw water. As for the poor, who formed the vast majority of the population, their water came in buckets, often from a faraway source, and had to be heated. Keeping clean was both time-consuming and expensive. In short, if the streets reeked, horses were only one part of the problem.

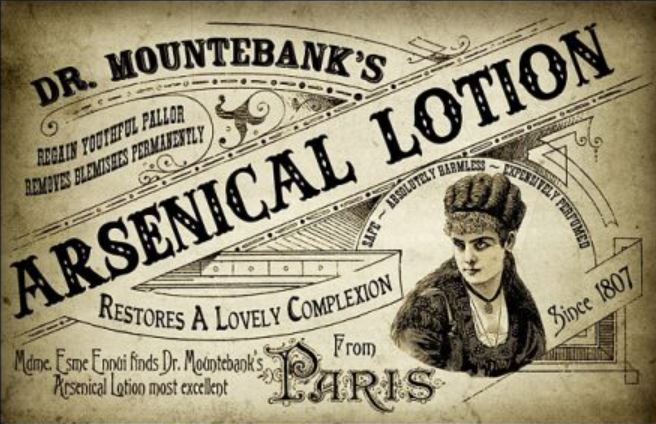

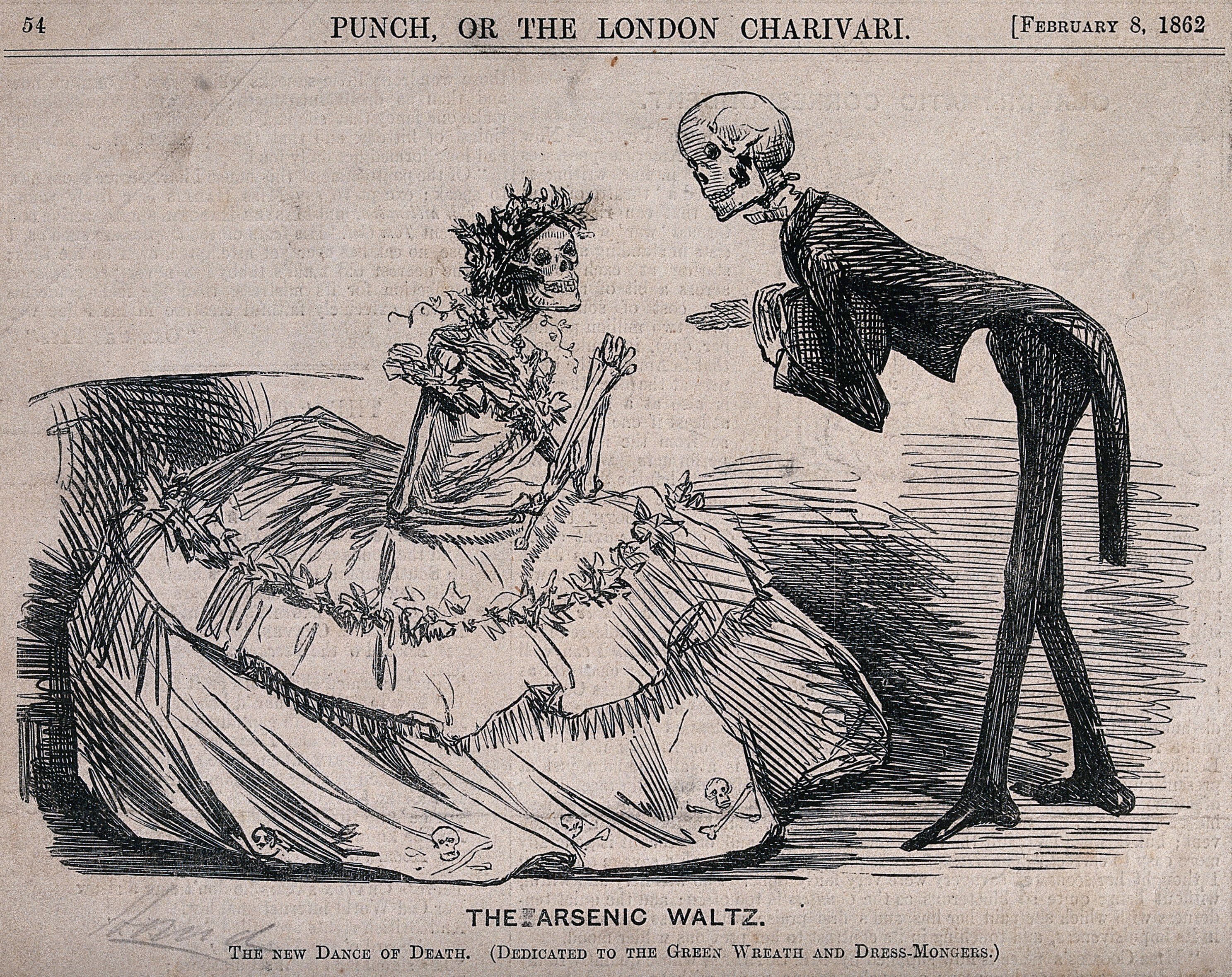

Food could kill you. No refrigeration meant that animal products spoiled rapidly. Little or no food control made eating hazardous to your health. Adulteration with unhealthy substances was not uncommon. The post Extreme Food Recycling depicts the brutal situation. (Warning: do not read it before, during, or immediately after a meal.)

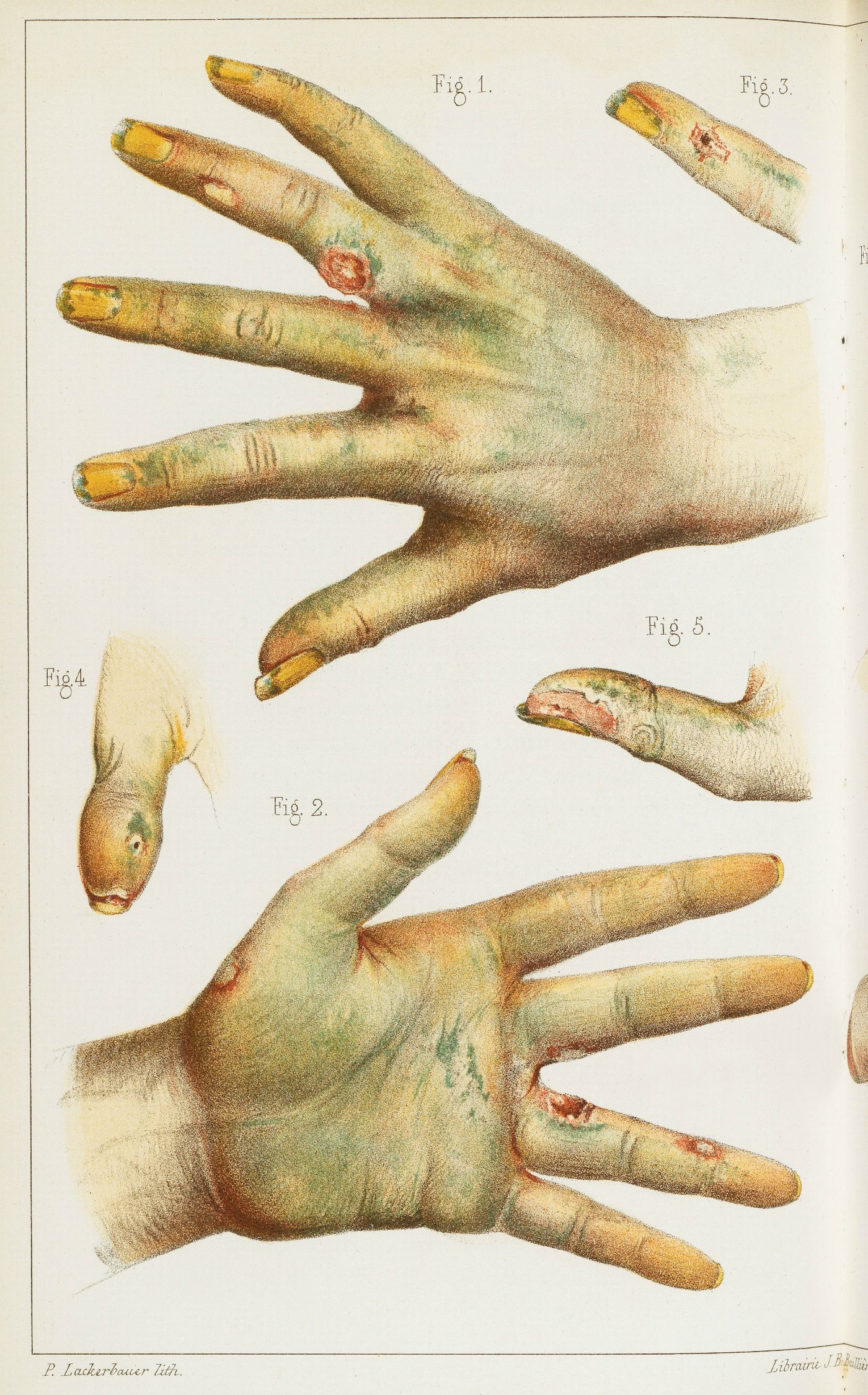

This lack of hygiene had consequences. Illness and premature death were ever present, with the average life-span only a half of what it is today. If you were unlucky enough to fall ill, you would stay in bed and send for a doctor. He would, in all probability, bleed you and prescribe some drops or powders to take in your drink. The rest was up to you.

.

.

Hospitals were for the utterly destitute and no one in their right mind would go near one. Except perhaps for an urgent amputation, which in many cases resulted in death by sepsis, or a heart failure because of the searing pain for which there was no relief. Instead of washing their hands and wearing protective clothing, surgeons operated in their street clothes and an apron coated with dried blood. They washed their hands after the surgery.

.

.

The plodding history of French hospitals/hospices under the Ancient Regime (pre-1789) was interrupted by the radical hand of the Revolution. In the Year II (1794), these institutions were nationalized. Only four years later, the revolutionaries realized they were unable to cope with the overwhelming task of poverty, and they dropped hospitals into the care of the municipalities who housed them. There they remained. Two centuries later, the mayor is still the chairman of the hospital’s board of directors.

Of the Ancient Regime hospitals in Paris, the largest was La Salpêtrière. It was an infamous women’s asylum, which was operated more like a prison, housing prostitutes, the mentally ill, and the disabled. It had a terrible reputation. During the Revolution, in 1792, the hospital was stormed with the intention of releasing the detained women. However, the situation got out of hand. Instead, the mob dragged out thirty-five of the women and murdered them. In the next century, the female inmates were exploited in the study of hysteria. (Professor Charcot and the Amplification of Hysteria and The Ball of the Folles.)

.

.

Around the mid-century, things began to change with the invention of anesthesia. It was now possible to cut patients open and repair them from the inside. Thanks to scientists Semmelweiss, Lister, and Pasteur, the knowledge of harmful bacteria resulted in improved cleanliness. Now it made more sense, even for the moneyed, to seek help at the hospital. And you needed money when you had the bad luck to be admitted into a secular establishment.

In the hospitals run by the religious authorities, and staffed by dedicated nuns, the patients were more or less equal. Not so in the secular hospitals, where those who could pay received all the attention while those who had no money got next to none. It took many years and many changes before patient care reached anything close to today’s standards.

.

The lay staff of the hospitals includes the ward maids, the

probationers, and the superintendents. The ward maids do

all the hard work. They sweep, make the beds (as badly as

possible), distribute and change the plates at meal-times,

cut up the bread, and live in a perpetual state of hostility to

the probationers, with whom they desire to be on an

equality. From this feeling arise continual quarrels and

complaints, in which the patients are often compelled to

take part, to their great disadvantage.

.

The ward maids are strong girls from the country, stupid,

coarse and rough, inconceivably awkward, if by an evil

chance they are called upon to give any help to a patient.

Their aim is to get through their work as quickly as possible,

to meet and gossip in their refectory. They are inveterate

beggars, and are always on the look-out to wring a few sous

from the patients. Everything must be paid for — a commis-

sion, a letter to the post; they smuggle in tobacco

and alcohol — in spite of a rule which absolutely forbids

gratuities. They are utterly indifferent to the patients, as

are nine out of ten of all the lay hospital assistants.

One of our friends knew an unfortunate man with a wound

in the leg, unable to go to the lavatory, and who for three

days asked in vain for a basin of water — he had no money.

The ward maids are boarded and lodged at the hospital.

They earn twenty to twenty-five francs per month, and

they have a free day once a fortnight.

.

The probationers (boursières) are young girls of from

twenty to twenty-five. Very often they are pretty. They

have influence, and are recommended to their posts. They

receive some rudimentary training in dispensing, obstetrics,

and medicine, also in dressing and bandaging. In theory,

they are on the same footing as the ward maids, but not in

practice. As the superintendents are recruited from their

ranks they receive superior consideration. Their duties are

to give out the medicine, &c., at fixed hours, to renew

dressings, to apportion to the patients their proper food,

and to watch the serious cases at night. They are required

to make the rounds frequently, to watch the dying, lay out

the dead, open and shut the windows at fixed hours, and

see that everything is clean. They fulfil these duties with

great indifference. If they dislike a patient they manage

to forget the hour for his medicine, and it is a lucky

chance if they do not make mistakes and poison some poor

creature committed to their care.

.

These statements are not exaggerated, and may be proved

any day in every hospital in Paris. The probationers spend

most of their time laughing and flirting with the house-

surgeons, dressers, or visitors. In this they are particularly

successful. They do not behave much better during the

doctor’s visits and as they pay little or no attention to his

orders, it is not surprising if they make blunders. They

take their meals outside, except when they are on duty,

which is twenty-four hours in three days, and sleep at home

except when on night duty. They are dressed like the ward

maids and superintendents, in a black dress, white apron

with bib, white sleeves, and a white cap with white bow.

The head-superintendents have a black bow on the cap.

Their name of boursières comes from the remuneration,

called a bourse, given by the Municipal Council, of 125

francs per month. They have a free day once a week.

When they are on night duty, they take part in convivial

parties given by the house-surgeons, and have a gay and

merry time. In a certain hospital which we will not name,

where a poet friend was a patient, the house-surgeons and

boursières on Shrove Tuesday romped in fancy dress through

the wards where men were dying — a most edifying spectacle.

.

The superintendent is an old probationer nominated

after several competitive examinations. She has the direction

of a ward and entire command of all the male and female

staff attached to it, under the control of the house-surgeon.

Her duties are not heavy, consisting only in the distribution

of wine and the dressing of some cases where the relatives

have paid her specially. She is, as a rule, a sharp, scolding,

authoritative person. She has no love for the boursières

and annoys them as much as possible. She worries

the ward maids without any mercy. She has a small room

to herself at the entrance of the ward, where she keeps her

notes and where she retires to gossip with the superinten-

dents of the other wards. She, like all the others, has no

real compassion in her. She does what is strictly necessary

— nothing more; she has no love for her patients. Her

profession is, for her, both dull and disagreeable — and she

takes all the hours of liberty she can get. She is often

married and receives a salary of about 1200 to 1600 francs

a year. Like the probationers, she leaves the task of

laying-out the dead to the ward maids.

.

We are not exaggerating the state of things, and moreover it is quite

comprehensible — these women have their interests outside

the hospital, their family, their friends. They go out often,

they draw a salary necessary to them for their living. It is

therefore a logical conclusion that they are not specially

enthusiastic about a very depressing profession, which

demands constant devotion of the most exalted kind.

.

If you like these posts, support the author by buying her books (available in print and in Kindle)

.

.

.

.