One hundred years before the Euro Disney, the Paris morgue was a popular attraction both for locals and tourists.

(From Paris Partout! A guide for the English and American Traveller in 1869 or How to see PARIS for 5 guineas)

Passing over the profusion of churches, monuments, galleries, and sights familiar to every tourist, we would draw the visitor’s attention to the MARCH OF IMPROVEMENT evidenced by this great city. In every quarter, at every level, Paris rises astonishingly anew. The sentimental antiquarian may mourn the loss of old Paris and its romantic past; the strict moralist may deplore the glory accorded to Mammon throughout, but others must justly rejoice at the triumph of modern science and hygiene.

The wonders begin at the lowest level: Paris’s new system of sewers consists of six main lines, fed by fifteen secondary lies, by means of which the city’s whole storm drainage is conducted to a grand receptacle beneath the Place de la Concorde, whence it is discharged by a shaft – the most extraordinary of its kind – sixteen feet high, eighteen feet wide, and three miles in length. The sewers may be visited, via an opening in the Boulevard de Sébastopol.

The foot pavement may also be remarked upon. Twenty-five years ago, it was detestable, worse even than London’s, and consisting in great part of large uneven stones, slopping from the houses down to the middle of the road, along which ran a copious and noxious gutter. The city is now widely blessed with smooth coatings of asphalt.

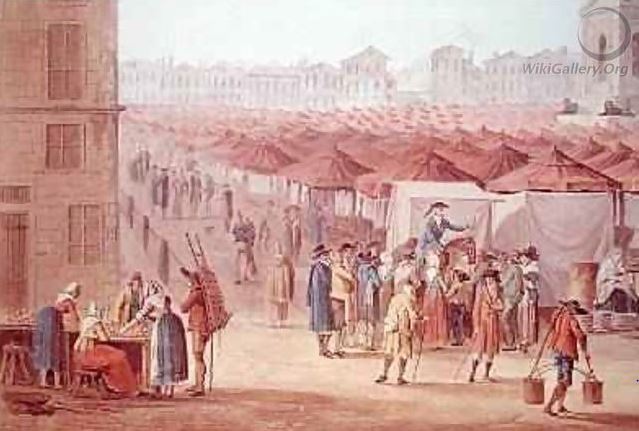

Les Halles market - the food cathedral. An example of the Industrial Age architecture.

Les Halles. An immense establishment, adjoining the old Marché des Innocents, on which the market people had constructed a set of wretched huts that continued to form Paris’s central market until very lately. In 1852 the present commodious and elegant Halles were begun from the architectural plans of M. Baltard, the result being eight large, lofty, and handsome pavillons, intersected by carriageways and joined by one immense roof of iron framing and glass covering. One pavilion serves as a fish-market, another poultry, another fruit and flowers, a fourth for butter, cheese, and eggs, two for butcher’s meat &c. The vaults below, which may be visited, contain marble tanks and fountains for live fish, and underground tramways to the railway termini, by which produce is brought in from the country and rubbish removed without encumbering the streets. The whole site extends over five acres and has cost in excess of £l,500,000. Four million bricks in the vaulting alone, and five million kilogrammes of iron were used in the whole construction. There are eight electric clocks, public conveniences, and extensive gas lighting.

Bois de Boulogne - to see and to be seen

Bois de Boulogne, four miles west of the Louvre. This favourite promenade was up to 1852 a regular forest, with walks and rides cut through. In 1852 the Emperor, determined to copy, or rather improve upon, the London parks, presented the Bois to the city of Paris, and, in concert with the Municipality, dug out the lakes, and made the waterfalls, raised mounds, traced new roads, and converted the whole into the present and popular place of public resort.

At the north angle, near the Porte de Sablons, five acres have been given over to the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimatation. Here are no wild beasts in the usual sense of the term, but only animals which may possibly be usefully acclimatized: yaks, tapirs, hemiones, viculas etc. Hitherto only lama and the Tibetan ox have succeeded. There are pretty views from the crevices of artificial rockwork which has been reconstructed for wild goats and mouflons. Eggs, and cuttings and seedlings from the exotic flora with which the garden is planted, may be purchased.

La Morgue, Quai Napoléon. The lower orders in Paris are fond of theatrical horrors, but it is not easy to understand how so repulsive a phenomenon, rebuilt in 1864, can be tolerated in a civilized country. Entering this building, one sees a glazed partition behind which stand two rows of black marble tables, inclined toward the spectator and each cooled by a constant stream of water. On these tables are exposed cadavers of those found dead or drowned, naked except for a strip of leather across their loins. Each corpse, often hideously bloated or disfigured, is thus left for three or four days, awaiting the identification of friends or family. Along the walls are hanged clothes and defects of the defunct. In 1866 the Morgue received a record 733 corpses – 486 men, 86 women, 161 infants. Of these 445 were identified; 285 had committed suicide by drowning, 19 were homicidal victims, 36 were hanged, 5 had shot themselves, 3 had been knifed, 6 charcoaled, 6 poisoned, 3 starved, and 82 had died suddenly in the street. Failed speculation on the Stock Exchange is said to be the greatest cause of suicide.

What, one must ask, is the use of such a monstrous proceeding? Few, surely, would recognize their oldest friend, naked, wet, and stretched out on a marble slab; and there are, in fact, numerous cases of persons not identifying their nearest relations, while others have wrongly laid claim to someone they knew not. A perpetual throng runs in and out of this loathsome exhibition, too many of them English and American tourists. There they stand, gazing at the hideous objects before them, sometimes with exclamations of horror, sometimes with utter vicious indifference. A poor madman, who fancies himself dead, comes every morning to see if he can recognize his own corpse, and is hardly to be driven away.

Next:Part 8 – Beware!

Read Full Post »

.

.